A work of literature can never be separated from the politics of its time - or so the academics claim. During my English degree, one professor spent an hour-long lecture analysing the apparent absence of the Rhodesian civil war in Tsitsi Dangarembga’s Nervous Conditions. They discovered allusions to the conflict in the most innocuous phrasings - and made a hell of a convincing case - but failed to consider the obvious: that this subject was of no interest to the author. A coming-of-age story, 1960s misogyny under the microscope, an ode to education, a scrutiny of post-colonialism, why does Nervous Conditions need to be a war story as well? You can find connections to anything if you contrive them, but it’s this kind of reductive thinking (or Essentialism) that is killing art for art’s sake.

BookTok is too convenient a culprit, a symptom of a wider contagion but not its root cause. Literature that garners the attention of the internet isn’t automatically bad, but condensing novels into thirty-second adverts has led consumers to perceive blurbs as checkbox exercises, ensuring their next read is crammed with the same themes and plot-points as their last. Female-centred or queer-coded retellings of classic Greek myths repeatedly make bestseller lists. And the abundance of pornography disguised as fantasy led to this viral comment on a Dostoyevsky reel: “White nights contains any smut or not?” Social media’s dilution of literary discourse into marketable tropes is just one facet of this essay. ‘High-brow’ fiction, the kind that wins literary prizes, is as guilty of pigeon-holing itself as any BookTok favourite. While avoiding the internet’s darlings - “enemies to lovers” and “there’s only one bed” - popular literary fiction uses the politics of identity as a crutch to absolve itself of the duty to tell fresh and interesting stories.

Stories don’t have to be timely or political to be necessary, but the scope to tell tales for the joy of telling them seems to be narrowing. Words like “vital” and “important” crop up on every other book cover, as if these signifiers carry more weight to a buyer than a functional blurb. Major publishing houses print more works than they can promote, which is why most debuts never recoup their advances. The runaway successes, however, the novels that Penguin and Faber blow their marketing budgets on, are overwhelmingly concerned with the politics of identity. Once upon a time, it might have been scandalous to scrutinise the contemporary political climate through fiction’s lens, now it’s a cheap shortcut to a literary prize’s longlist. Disclaimer: this isn’t going to be another tirade from a straight white bloke blaming market trends for his unpublished novel; rather, this is an interrogation of the kinds of stories publishers are willing to sell.

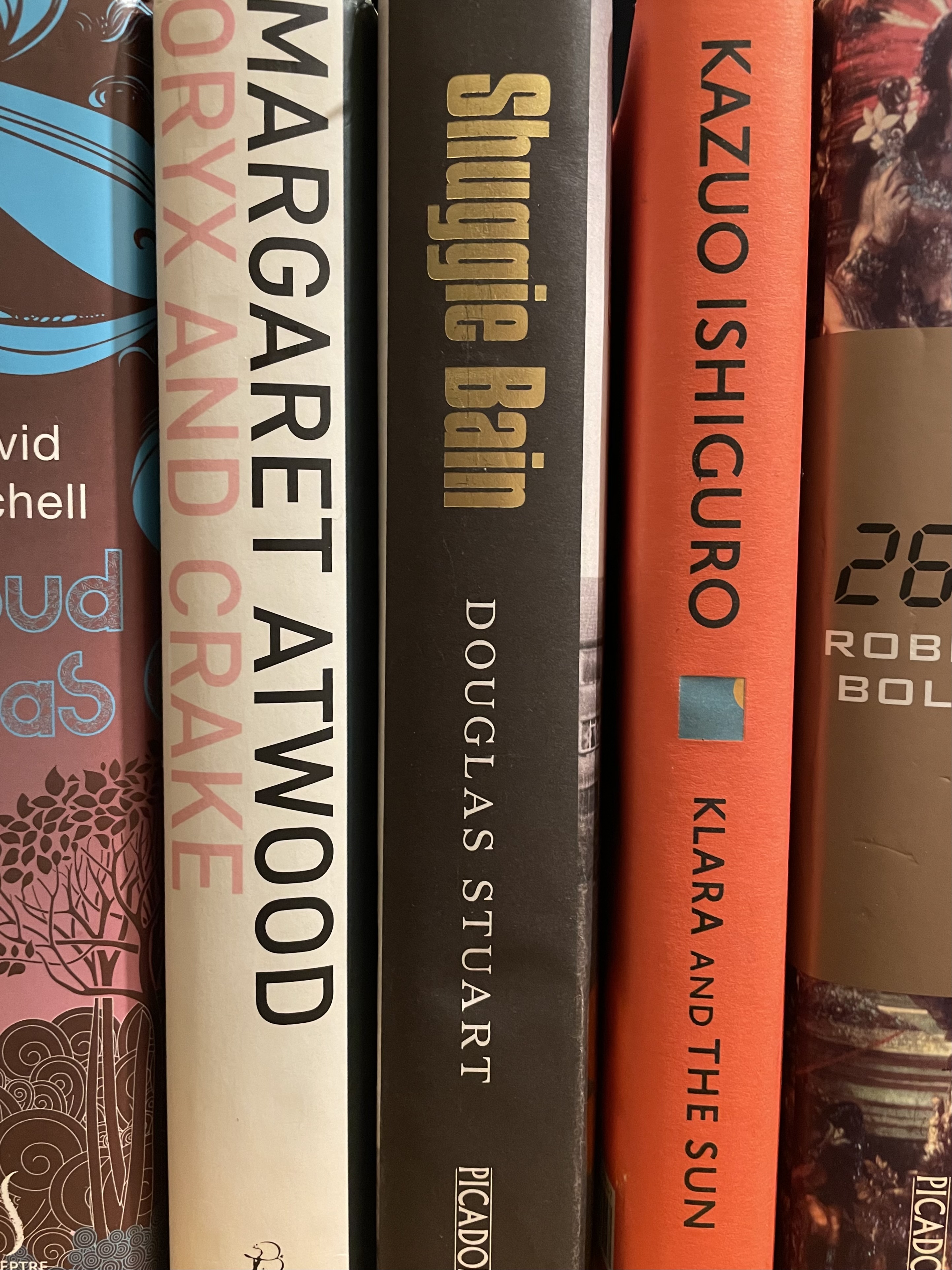

Douglas Stuart is a prime example. Shuggie Bain, his 2020 debut, won the Booker Prize that year and earned a special place in readers’ hearts, mine included. I looked forward to his follow-up, Young Mungo, and upon release it enjoyed similar acclaim to its predecessor. For me, however, it fell short. The subtleties of Stuart’s debut were gone: similes were overwrought, characters were flat, and their traumas seemed cherry-picked for audiences who want to try on hardship like a sibling’s clothes. My biggest issue with Young Mungo was its reliance on Shuggie Bain’s blueprint. Focusing on a marginally older protagonist, themes of repressed homosexuality and alcoholism were repeated, but without the nuances of his debut. Events were more brutal, more shocking, but shallower. I could almost visualise Stuart gleefully penning his grotesquest scenes, drawn out in his signature poetic prose, passages so artfully horrible they ceased to feel real. In fact, they felt safe, as if Stuart was writing to a formula for tried and tested Booker-winning success. He’s made no secret of the fact that his works of fiction about gay young men in post-Thatcherite Glasgow are inspired by his lived experience as a gay young man in post-Thatcherite Glasgow. But is Stuart permitted by his audience to write, for example, a war story or to dabble in magical realism? Will Picador be as keen to pick up his next novel if it doesn’t fit the mould?

This essay’s premise was conceived when I watched American Fiction last year. “A frustrated novelist, fed up with the establishment profiting from ‘Black’ entertainment that relies on tired and offensive tropes, uses a pen name to write his own outlandish ‘Black’ book”, its Amazon synopsis reads. One memorable scene sees Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison finding his works in the ‘African-American Studies’ section of a bookstore. “They’re just literature,” he tells the employee, “the blackest thing about this one is the ink.” In another scene, his agent uses three bottles of Johnny Walker - Red, Black, and Blue - to analogise the difference between a quality product and a popular one. A complex, challenging novel sells fewer copies than a quick read because, “at the end of the day, most people just want to get drunk.” Only when Monk performs a particular type of ‘Blackness’, one incongruous to his Upper-Middle Class upbringing, does his work begin to resonate with White audiences.

American Fiction’s subject matter, as well as being conveniently applicable to the contemporary publishing landscape, made me recall Green Book’s critical reception following its 2019 Oscar win. Spike Lee famously said the film wasn’t his “cup of tea” after the ceremony. Critics latched onto his disdain, and Green Book soon topped lists of ‘worst Oscar winners’ for propagating yet another ‘White saviour narrative’. The discourse around Green Book centred on whether it was correct for a white man to direct this kind of story, to the extent that most of its critiques were less informed by its plot than the racial politics of its creation. During an Actor’s Roundtable interview, The Hollywood Reporter took issue with Viggo Mortenson, Green Book’s lead actor, claiming there’s no character he wouldn’t play. Determined to catch him out, they asked if he’d play Othello, a character traditionally performed in blackface. Mortenson admitted he wouldn’t. Then he countered: “Would it be okay if Mahershala Ali fell madly in love with a short story about Scottish immigrants who become cowboys? Is there anything wrong with him directing a samurai movie?” Silence proved his point. American Fiction and Green Book have different purposes, but I group them because the criticisms surrounding the latter’s creation directly correspond with the former’s thematic core. The tick-box exercise of Green Book’s press tour is exactly the kind of Essentialism that American Fiction’s Thelonious ‘Monk’ Ellison rebels against.

Hollywood is a single purveyor of the return of the archetype, a trend encountered as frequently in novels. By definition, literary fiction prioritises character over plot, but the characters we meet are increasingly defined by what they are, rather than who they are; personality is a loose pencil sketch over which identity can be painted. Let’s compare the opening lines of the blurbs of Douglas Stuart’s two novels. First, Shuggie Bain: “Agnes Bain had always expected more. In the Glasgow of the early 80s, she dreamed of greater things.” And now, Young Mungo: “Born under different stars, Protestant Mungo and Catholic James live in a hyper-masculine world.” In fewer than twenty words, a reader gets a fairly good idea of who Agnes Bain is; by contrast, Mungo and James become portraits without faces.

As the 2020s progress, novels rely on clear branding. I’d be naive to dismiss the sheer volume of new published works as the most significant factor: it’s good business in 2025 to slap your book’s ideological purpose on the cover in the hope it becomes a juicy TikTok soundbite. But I increasingly find myself dismissing titles after a quick scan of the blurb. I don’t want to be told directly what a book is trying to achieve, or what emotions I am supposed to feel while reading it. Novels pitch themselves to imagined readers who’ll identify with the protagonist. Retelling The Iliad from yet another ‘fresh’ perspective, for example, isn’t high art. Homer might not have existed, Troy might not have existed, and Oddyseus and Achilles almost certainly never existed. The story of The Iliad is deeply ingrained in our culture (take a look at your heel) but I have no interest in reading a Gen Z-friendly version of an almost three-thousand-year-old epic poem that’s already been adapted countless times.

Greek myths are a popular victim, but Homer’s works aren’t an isolated case. Fiction is more socially engaged than it used to be - that’s no bad thing - but I’m seeing a pattern of novels mimicking what literary criticism has been doing for decades, applying a theoretical lens to works of literature and rewriting them for ‘modern audiences’. 2023 saw the release of Sandra Newman’s Julia, a retelling of George Orwell’s 1984 from the female character’s perspective. I read 1984 at university, along with enough engaging feminist criticism to have no interest in reading a novelistic version of what’s already been the subject of rigorous academic discussion. The same thing happened last year with Percival Everett’s James, which tells the story of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn from Jim’s point of view. One doesn’t need to have studied Postcolonial literature to take issue with Twain’s problematic portrayal of an escaped slave. For me, they’re novels that have no reason to exist, offering already universally agreed conclusions about depictions of women and people of colour in classic literature. In fact, I would go a step further and argue these novels undermine work done by scholars who approach identity in inventive ways, rather than reinforcing the idea that identities - ‘a woman’, ‘a queer person’, ‘a black person’ - are something ‘Other’. Furthermore, I cannot fathom why, if you are in the privileged enough position to publish a novel, you’d want it to be a facsimile of someone else’s work. Both Julia and James found wide readership and critical acclaim. The latter was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, and the former is considered in some circles to be an essential companion piece to the reading of Orwell’s original novel from the ‘40s. I’m not bashing their merits as works of literature; I only wonder if these retellings will stand the test of time like their inspirations have.

My purpose with this essay isn’t to decry every work of fiction published in the last decade. Trends produce outliers. When considering exceptions, Max Porter is the first name that springs to mind. Since 2015, he’s published four novels, each as different as the last: Ted Hughes’s character Crow as a metaphor for grief; a folk horror set in rural England; a study of Francis Bacon’s final days; and one night in the life of a troubled young man - aside from Porter’s characteristic lyricism, there’s little to link his titles. All have been released by Faber, a major publisher, and have accrued critical and commercial acclaim. In fact, at least half of Porter’s novels have had their rights acquired for film. These are luxuries usually enjoyed by established authors, those who have the freedom to make art for art’s sake because their names automatically sell copies. Margaret Atwood, Kazuo Ishiguro, and David Mitchell traverse genres and refuse pigeon-holes, but their debuts all came out decades ago. Major publishers aren’t queuing to represent new writers with difficult-to-market stories. Porter’s success was unexpected, aided somewhat perhaps by his previous career as a bookseller, but it speaks to the appetite of a wider audience; publishing houses with significant budgets could do worse than taking a chance on debut authors for whom politics and identity are secondary to original ideas. They might just end up with another bestseller.

Publishing anything is a gamble. Supposed safe bets - like a £2 million advance for Boris Johnson’s memoir - can lead to thousands of copies ‘reduced to clear’. Comparatively, a few grand chucked at a no-name author isn’t much of a loss if the book doesn’t sell. Unless you’re an Indie publisher, that is. Bold, scrappy, self-sufficient and willing to take risks on titles the Big 5 can’t be arsed to market, Indie presses have risen in popularity over the last decade. In Liverpool, Dead Ink Books advertises itself as “unsatisfied with the mainstream”, and their roster of authors is responsible for experimental and award-winning books. But, in the grand scheme of things, they aren’t widely read. There is a disparity between what is regarded as quality literature and what sells copies; with major publishers, the disparity is smaller. People are more likely to pick up a ‘high brow’ novel if it comes with a stamp of endorsement on the spine from HarperCollins or Simon & Schuster. And, while high street retailers like Waterstones do stock Indie releases, they’re unlikely to feature in the carefully curated displays that catch customers’ eyes.

I could lazily draw the conclusion here that Literature with a capital L has simply had its day. Only half of the UK’s adults claimed to read for pleasure in 2024. In the same year, according to The Reading Agency, a quarter of 16-24 year olds admitted they’ve never been readers. There’s a flipside to this depressing statistic. The focal points of my argument - reliance on Essentialism, repetitive rehashings of familiar tales, and the TikTokisation of reading - are English-language phenomena. Around the world, incredible works of fiction are being written and read in languages other than English. Fitzcarraldo Editions, a London-based publisher founded in 2014, specialises in publishing the highest quality fiction in translation. It’s a business model that has so far secured them four Nobel Laureates, as well as introducing the English-speaking market to a host of names already celebrated in Europe, Asia, and Latin America.

If the Nobel’s judges refuse to succumb to the trite and the uninspired, then so should we. Novels are supposed to teach us things, lessons deeper than polished, mass-market friendly accounts of what it means to be a man or a woman or neither, or gay, or a person of colour. Varying perspectives are integral to world-class literature in translation, but their writers don’t rest on the assumed laurels of an exotic-to-the-English-reader protagonist. Identity, and the politics attached, can never be a whole story. It’s only in the English-speaking world that we have stopped asking for the rest.